Poiesis as referred to in the ELC1 is a term used to describe the continual construction of the electronic environment by its creators and receivers. Two additional works that I have chosen for discussion include: ‘Cruising’ by Ingrid Ankerson and Megan Sapnar, and ‘Girls’ Day Out’ by Kerry Lawrynovicz. These works serve as forms of electronic poetry that use poietic strategies to reveal their various meanings.

Tag Archives: Cruising

Cruisin’ with “Cruising”

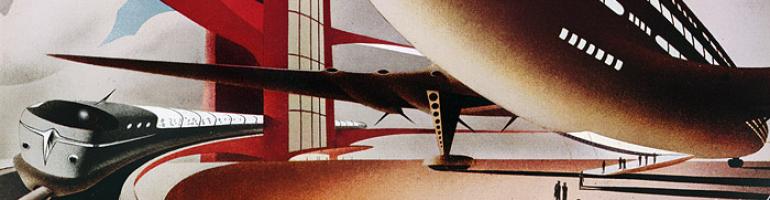

“Cruising” by Ingrid Ankerson and Megan Sapnar is an electronic, reader-controlled piece of literature that combines written word, image and sound. It is the manipulation of the reader’s tactile, visual and auditory senses that make the poem effective and quite enjoyable. “Cruising” is about the ritualistic activity of driving in a vehicle up and down the main street of a small town seeking excitement, and feeling desperate to quell the boredom that comes with being young in Wisconsin. The keyword “Place” is one that stuck out in my mind, as it is applicable to this poem in a number of ways.

The reader must learn the skill of mouse placement in order to view the e-lit piece effectively. The first time reader will realize that the mouse being placed too high or low or left or right will greatly impair their ability to read the words or view the images being displayed in this piece. It is the mastering of this skill that allows the reader to fully enjoy the poem. Although Sapnar and Ankerson offer the reader some level of interactivity they limit the ability to self-stop and start the word flow. It is my understanding that this control is based on the authors need to maintain the idea behind the story. The characters are driving, and as they are moving the reader should move with them. The fact that a simple hand slip drives the poem faster really evokes a certain feeling in the reader, the feeling that they too are in the car and they are moving with the characters.

The jovial music plays, and the sound of the narrator’s voice is youthful and excited. It is as though the viewer is there, in small town Wisconsin, where the highlight of a Friday night is a flirtation between two car windows and an opportunity to (maybe) smudge that pink lipstick. The authors did a brilliant job in making sure that place was communicated effectively, and I believe that it was their intention to use such an innocent, excited voice to emphasize the age of the characters and the need for excitement in the town the story is set in.

All in all I would recommend this piece. “Cruising” was heartwarming. The description of place in regards to the viewer’s hand placement and the place where the story is set were well executed. Reading, watching and listening to this poem made me feel like I was there.

Filed under Review

Response to “Cruising” questions

Hi everyone, thanks for your excellent questions. And thank you Aurelea for selecting our work and for inviting me to virtually participate in your class. This blog is a great idea, and I truly enjoyed sharing some of the background on Cruising with the class and hearing your questions. I hope my responses answer your questions sufficiently!

1. How would you classify “Cruising” ? As a whole what categories do you feel exist in E-Poetry at present?

This is a tough question to answer because there are so many overlapping terms and different ways artists and poets talk about their work. I once interviewed the late Argentine visual poet Ana Maria Uribe who referred to her work as “anipoems.” And I’ve heard categories like “codework,” “generative writing,” “combinatory forms,” “kinetic poetry,” “flash poetry,” and the list goes on. Many of these are keywords used in ELC1. Cruising is difficult to classify because our concept in creating the work was to blur categories, for example mixing nonlinear interactivity (the text/images) with linear/time based components (the voice recording). Maybe it’s a reactive/nonlinear/time-based/spoken word/interactive/new media poem. I saw that the key words ELC1 uses to describe Cruising include audio, collaboration, flash, place, poetry, visual poetry or narrative, and women authors. While I wouldn’t disagree with any of these terms, I wouldn’t say that any of them best characterize Cruising either. I think the usefulness of the keywords comes from the different ways that works get clustered; it offers different windows into the range of, say, audio pieces, or work made in Flash.

Usually my work has been classified as “Flash poetry,” but I don’t think that the software program used to create the work says the most about the poet’s intentions, or the concepts being explored in the work. Maybe we need a combination of key words and reader folksonomies; that way multiple overlapping categories would come from both top-down and bottom-up systems.

2. Why did you decide to change your style from having less reader interaction to full user interaction? Did you find it to be more visually appealing? What was the motivation behind it?

It’s not that we changed our style, we were just interested in exploring different questions in Cruising. This wasn’t an attempt to be more visually appealing, but rather to explore the ways that linear and nonlinear components can exist and conflict and support one another in a single work.

3. Back in 2000 open-source programs were not as capable as they are now. Do you see yourself using an open-source option in the future rather than Flash?

I always used Flash because I came to know it well; and once I had a grasp on the program, it was easier to do the things I wanted to do without re-learning how to do simple things. I would be interested in mastering other production software, including open source solutions, because I think that new applications (and the accompanying code, interface, and production ideologies) would inspire new ways of thinking about the possibilities of new media for literature and art. That said, even software like Flash has changed significantly since 2000. OSFlash is a thriving Open Source Flash community.

4. Why did you decide to change the piece from a love poem to a poem about adolescence?

This is a really good question. Ingrid and I were talking about it this morning as we realized that it’s sometimes hard to remember exactly why we made the decisions that we did. Ultimately, it’s not that we changed it from a love poem as much as we wanted the poem to have a more open-ended conclusion, one that supported the endless, repetitive act of cruising. The ending to the original poem moved from cruising small-town Wisconsin as a teenager to driving silently with someone that you love, windows down, the night air rolling by, and being utterly sure of yourself. This ending was very “complete” in a way that we didn’t want our reactive/nonlinear/time-based/spoken word/interactive/new media poem to be. Instead, we wanted to play with the metaphor of the night rolling by like movie credits. We visually arranged the images like they existed on a piece of film; but instead of the linear animated techniques that demanded stasis from the viewer (as a movie does), we instead wanted the poem to demand activity from the reader. It is through the activity of driving the interface that words and themes become connected.

5. How does the theme of struggle relate to your poem?

This is another really good question. I mentioned in my original post that the audio recording and the nonlinear interactive aspect represented a struggle between the speaker and the reader. But perhaps the greater struggle exists in the relationship between the themes and the forms of interactivity. On one hand, adolescence is a struggle; learning to drive is a struggle; learning to read is a struggle; trying to figure out what a poem means, what life means, etc.—it’s all a struggle! By making it difficult to control the speed, size, and flow of text and images, we wanted to highlight the work a reader must do to make a poem meaningful. Of course, there is more than one way to read a poem and different readers will create different meanings. Perhaps the goal is to find the lines of text being spoken at that moment and have them coincide with the audio. Or maybe, for a different reader, the goal is to go as fast as you possibly can until the blur of images are tiny, unrecognizable patterns.

6. Are you worried about losing the poem/words/text within the other multimedia elements that are central to “Cruising”?

No. In fact “losing” the poem/words/text (if you’re referring to the reactive component that the reader manipulates) is what is central to Cruising. True, there is a lot going on here: moving the mouse to the top of the screen pulls the text closer, which makes it easier to read. Moving the mouse to the bottom pushes the text away, making it too small to read. Moving to the left or right controls the direction and speed. Learning to navigate these multiple elements, in coordination with the voice track, takes some work. But illuminating this work is one of the major goals of the poem.

Learning to Drive Digital Poetry

It is a Tuesday afternoon in October and two dozen English 214 students at Capilano University have been driving Megan Sapnar Ankerson and Ingrid Ankerson’s poem “Cruising” since Sunday night. “Cruising” was first published on the new media poetry site Poems That Go. It was later selected to appear in the Electronic Literature Organization’s Electronic Literature Collection, Volume 1. This is where the English 214 students first encountered the poem.

Today’s we began by trading interpretations and readings of “Cruising.” The class then tackled Megan’s “On Cruising” from Sunday, October 18th which offered us a behind the scenes look at the poem’s compositional history + the background story on Poems That Go. It was from these discussions that the six questions below emerged:

1. How would you classify “Cruising” ? As a whole what categories do you feel exist in E-Poetry at present?

2. Why did you decide to change your style from having less reader interaction to full user interaction? Did you find it to be more visually appealing? What was the motivation behind it?

3. Back in 2000 open-source programs were not as capable as they are now. Do you see yourself using an open-source option in the future rather than Flash?

4. Why did you decide to change the piece from a love poem to a poem about adolescence?

5. How does the theme of struggle relate to your poem?

6. Are you worried about losing the poem/words/text within the other multimedia elements that are central to “Cruising”?

These are but six of the many questions that were contenders for this forum. And we apologize for not narrowing the list down further. And so – Megan – pick the three or so that you are MOST interested in answering!

The Students of English 214

On “Cruising”

Behind the Scenes of Poems that Go

Cruising was published in the fifth issue of Poems that Go, the new media poetry journal that Ingrid and I started in the spring of 2000. Ingrid and I are partners in art and in life, and at that time we were also working together designing websites. Our mutual love of both poetry and web design lead to an interest in the possibilities of electronic literature and exploring the relationships between words, form, language, and code. On a whim and in a span of about three weeks, we registered the domain name, sent out solicitations, and launched the first issue.

The idea of Poems that Go got its roots in 1999 at a poetry reading at the Baltimore Book Festival. At the reading there was a very animated signer who, in one instance, transformed an average poem into a completely different animal. After the reading, we were both inspired by how this signer acted as an interface between the audience and the poet. His expressions were intense, exaggerated, wild, and his hands lifted the words and threw them into the air. The combination of reading and signing brought something new to the work that would not have been achieved by the reading alone. All of this started us thinking about exploring the ways multimedia could introduce another layer of signs to a poem.

The first issues of Poems that Go featured time-based work, all made with Flash, and all animated, cinematic-style pieces with a beginning, a middle, and an end (see for example, Car Wash and While Chopping Red Peppers). At the time, we were interested in presenting alternatives to hypertext and hypermedia. We looked for shorter works that relied extensively on visual media and we wanted to preserve the linearity of a poetry reading. I remember receiving some initial criticisms (“Why isn’t it clickable?” and “You fail to take advantage of the interactive possibilities of the web environment” ); but we saw the conscious decision to restrict interactivity as part of the work’s meaning.

In 2000, Flash was gaining a lot of attention, but it was also garnering a fair share of criticism for perpetuating “look what I can do” attitudes about web design. The dot-com bubble burst as we launched our first issue of Poems that Go, although we didn’t know this at the time. Many artists rejected proprietary software products like Flash because the closed-system went against the tradition of sharing and the open-source nature of the web. Ingrid and I liked Flash because it was easy to use and we had more control over images and sound with minimal knowledge of programming. The work we published in early issues of Poems that Go was somewhat anti-hypertext fiction, which we perceived as being too insular. We saw hypertext literature as a “closed system” because it was mainly read by other hypertext authors and literary scholars. So while there was not a big popular audience for hypertext literature, Ingrid and I , in our young, naive ways, wanted poetry for the masses. We were also curious about what it meant to force linearity on a hypertext world, to make beginnings, middles, and endings in a non-linear networked environment.

On Cruising

Although this initial question seemed like a good one, by our third issue we were ready to explore new ways of thinking about temporality. In 2001, while working on Cruising, we began combining time-based and reactive media in a single work. (Because we came from the worlds of graphic, web, and publications design we were more familiar with John Maeda’s concept of reactive media rather than Espen Aarseth’s notion of ergodic literature). The text of Cruising existed first on paper. Ingrid wrote it while she was in grad school studying Creative Writing and Publication Arts at the University of Baltimore. The original version, (which I will sheepishly admit was a love poem written for me), had a few extra lines leading to a different ending. With edits, we both felt the poem was a great candidate for a Poems that Go collaboration for experimenting with linearity and nonlinearity. And with the Baltimore Book Festival signer as a muse, we believed that new media could introduce a new symbolic layer to Cruising that would operate between the theme of the poem and the work of the reader.

Together we worked out the visual aesthetic for the piece, shooting the photographs and selecting images and a color scheme. We recorded Ingrid’s voice reading the piece, and went through several versions before we decided on the one that exists in the final version. (How do you think the poem would be different if we chose the first version that was recorded?)

I worked on the interface, which was an adaptation of Yugo Nakamura’s “slider menu” presented in the second version of his Mono*Crafts website. Yugo offered the source code of his navigation technique to the Flash community (while the technology is proprietary, Flash users often freely share code and advise). Early experimental Flash sites like Yugo’s presented navigation schemes as something that a user had a master, rather than as something “intuitive” and obvious. The notion of having to learn to use and master navigation fit well with the “driving” and navigation subject matter of Cruising. It was also a productive way for us to explore the relationship between reader and poet.

The interface is absolutely central to this piece; as the element that forms a boundary between two things, it highlights the work that a reader must do in order to make the poem meaningful. And unlike our earlier time-based work, where a reader passively sat and listened, Cruising borrows the reader’s action in order to pose questions about the relationships between words, themes, metaphors, and interaction. While the reader learns to control the pacing, direction, size and flow of text and images, the poem is read aloud. And while the guitar riff continues infinitely, the poem is only read once. We wanted to illustrate the ongoing and repetitive act of cruising, while at the same time presenting the struggle between the speaker and reader—fighting for control of the wheel, the landscape, the ride, the view, the poem. Ultimately, this is a story of just one person’s experience while cruising, which is why the spoken part of the piece is linear. But when this narrator’s story ends, the reader is free to continue “cruising” back and forth until they decide to end the poem.

Filed under Event